Market Maturity Methodology: Difference between revisions

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

=Overview of early adopter countries on the Global Digital Health Index= | =Overview of early adopter countries on the Global Digital Health Index= | ||

The 22 early adopter countries on the [https://www.digitalhealthindex.org/ Global Digital Health Index (GDHI)] opted onto the platform in order to use this benchmarking tool to track critical data on the status of each | The 22 early adopter countries on the [https://www.digitalhealthindex.org/ Global Digital Health Index (GDHI)] opted onto the platform in order to use this benchmarking tool to track critical data on the status of each country's digital health ecosystem, as well as to learn from the experience of other countries. The initial countries to participate, profiled in Table 1, included those who contributed to the design and testing of the GDHI by participating in the design workshops and testing the prototype version of the platform. GDHI also leveraged regional digital health networks such as the [http://www.aehin.org/ Asia eHealth Information Network (AeHIN)] to encourage member countries to participate and ensure a diverse set of countries across all regions are represented on GDHI. | ||

The GDHI countries are spread across five continents, with many in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Countries at different size, stages of economic growth and digital health development are represented, and while there is often a correlation between the GDP per capita of the country and their digital health ecosystem maturity, this is not always the case. For example, Malaysia has the most mature digital health ecosystem on GDHI even though it does not have the highest GDP per capita of the countries represented. | The GDHI countries are spread across five continents, with many in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Countries at different size, stages of economic growth and digital health development are represented, and while there is often a correlation between the GDP per capita of the country and their digital health ecosystem maturity, this is not always the case. For example, Malaysia has the most mature digital health ecosystem on GDHI even though it does not have the highest GDP per capita of the countries represented. | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

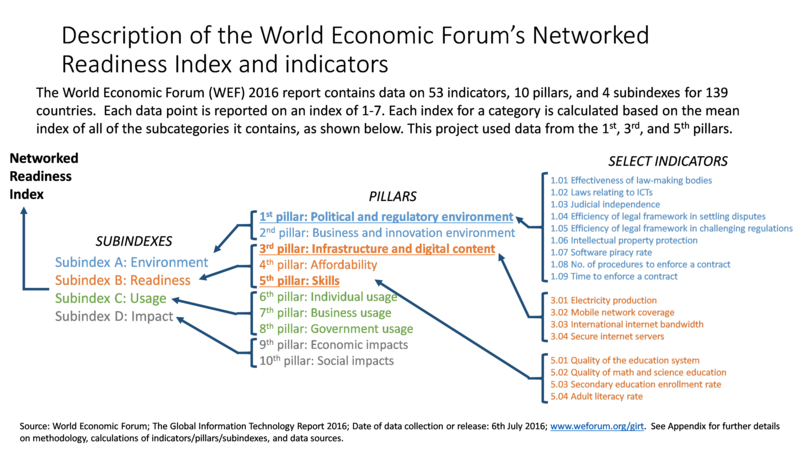

'''Figure 1: Comparative indicators for GDHI extension and reliability assessment''' | '''Figure 1: Comparative indicators for GDHI extension and reliability assessment''' | ||

[[File:Maturity.png | 800px]] | [[File:Maturity.png | 800px]] | ||

The three pillars selected for this analysis are the (1) political and regulatory environment, (2) infrastructure and digital content, and (3) skills . The political and regulatory environment pillar assesses the extent to which national legal frameworks promote ICT penetration and the safe development of ICT business practices. This includes intellectual property protection, software piracy rates, and efficiency of legal frameworks. The infrastructure and digital content pillar provides information on the ICT infrastructure including electricity, mobile network coverage, international bandwidth coverage, and secure internet servers. Lastly, the skills pillar evaluates the extent to which a society can effectively use and potentially benefit from ICT based on the quality of education, secondary education enrollment rate and literacy. | The three pillars selected for this analysis are the (1) political and regulatory environment, (2) infrastructure and digital content, and (3) skills . The political and regulatory environment pillar assesses the extent to which national legal frameworks promote ICT penetration and the safe development of ICT business practices. This includes intellectual property protection, software piracy rates, and efficiency of legal frameworks. The infrastructure and digital content pillar provides information on the ICT infrastructure including electricity, mobile network coverage, international bandwidth coverage, and secure internet servers. Lastly, the skills pillar evaluates the extent to which a society can effectively use and potentially benefit from ICT based on the quality of education, secondary education enrollment rate and literacy. | ||

'''Table 2: GDHI extension and reliability assessment indicators''' | '''Table 2: [http://index.digitalhealthindex.org/indicators_info GDHI extension and reliability assessment indicators]''' | ||

{| style="border-style: solid; border-width: 3px" class="wikitable" | {| style="border-style: solid; border-width: 3px" class="wikitable" | ||

| style="width: 10%;" | '''Indicator #''' | | style="width: 10%;" | '''Indicator #''' | ||

| Line 152: | Line 153: | ||

'''Figure 2: Maturity level comparison''' | '''Figure 2: Maturity level comparison''' | ||

[[File: | |||

[[File: Maturity v1.png | 800px]] | |||

=Discussion and Conclusion= | =Discussion and Conclusion= | ||

| Line 159: | Line 161: | ||

The new global digital health index, presented in this analysis, is a useful extension to the GDHI for several reasons. First, the analysis includes 139 countries as compared to the 22 currently captured in GDHI. Until more rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments are resourced and institutionalized, this model gives us an understanding of digital health maturity levels across a large cohort of countries. WEF indicators are uploaded annually, which is critical given the rapidly changing digital health field. Lastly, the new index does not exclusively rely on self-reported inputs making it an objective complement to self-assessment-based models. | The new global digital health index, presented in this analysis, is a useful extension to the GDHI for several reasons. First, the analysis includes 139 countries as compared to the 22 currently captured in GDHI. Until more rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments are resourced and institutionalized, this model gives us an understanding of digital health maturity levels across a large cohort of countries. WEF indicators are uploaded annually, which is critical given the rapidly changing digital health field. Lastly, the new index does not exclusively rely on self-reported inputs making it an objective complement to self-assessment-based models. | ||

Unfortunately, in a world without rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments, this model has major limitations that must be carefully considered when using this information. First, the WEF indicators capture cross-sectoral information and do not account for the health sector being more or less mature than the overall ICT sector in a given country. Second, a country-level analysis has some value, but a more granular analysis would likely reveal more actionable findings. For example, there can be large sub-national variations (e.g. urban vs rural). Third, | Unfortunately, in a world without rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments, this model has major limitations that must be carefully considered when using this information. First, the WEF indicators capture cross-sectoral information and do not account for the health sector being more or less mature than the overall ICT sector in a given country. Second, a country-level analysis has some value, but a more granular analysis would likely reveal more actionable findings. For example, there can be large sub-national variations (e.g. urban vs rural). Third, it's very possible that the concordance levels change as more countries contribute to the GDHI; 22 is not a large number and the correlation could look quite different if 50 or more countries contribute to the GDHI. | ||

While there is a reasonable agreement between the GDHI and the extension, additional research is needed to identify a more comprehensive list of indicators to assess digital health maturity. Our hope is that these analytics inspire further investment and engagement in developing a world-wide, annually measured indicator of country digital health maturity that factors in both self-reported and objective measures. | While there is a reasonable agreement between the GDHI and the extension, additional research is needed to identify a more comprehensive list of indicators to assess digital health maturity. Our hope is that these analytics inspire further investment and engagement in developing a world-wide, annually measured indicator of country digital health maturity that factors in both self-reported and objective measures. | ||

Latest revision as of 23:44, 5 May 2021

This page outlines the methodology used to

Overview of early adopter countries on the Global Digital Health Index

The 22 early adopter countries on the Global Digital Health Index (GDHI) opted onto the platform in order to use this benchmarking tool to track critical data on the status of each country's digital health ecosystem, as well as to learn from the experience of other countries. The initial countries to participate, profiled in Table 1, included those who contributed to the design and testing of the GDHI by participating in the design workshops and testing the prototype version of the platform. GDHI also leveraged regional digital health networks such as the Asia eHealth Information Network (AeHIN) to encourage member countries to participate and ensure a diverse set of countries across all regions are represented on GDHI.

The GDHI countries are spread across five continents, with many in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Countries at different size, stages of economic growth and digital health development are represented, and while there is often a correlation between the GDP per capita of the country and their digital health ecosystem maturity, this is not always the case. For example, Malaysia has the most mature digital health ecosystem on GDHI even though it does not have the highest GDP per capita of the countries represented.

Table 1: Overview of 22 early adopter countries of the GDHI

| Country | Population in millions, 2017 | GDP per capita, 2017 | Health expenditure as % of GDP (2016) | Life expectancy (2017) | % of population urban |

| East Asia & Pacific | |||||

| Indonesia | 263.99 | 3,847 | 3.1% | 71 | 55% |

| Lao PDR | 6.86 | 2,457 | 2.4% | 67 | 34% |

| Malaysia | 31.62 | 9,945 | 3.8% | 76 | 75% |

| Mongolia | 3.08 | 3,735 | 3.8% | 70 | 68% |

| New Zealand | 4.79 | 42,941 | 9.2% | 82 | 86% |

| Philippines | 104.92 | 2,989 | 4.4% | 71 | 47% |

| Thailand | 69.04 | 6,594 | 3.7% | 77 | 49% |

| Europe & Central Asia | |||||

| Portugal | 10.29 | 21,136 | 9.1% | 81 | 65% |

| Latin America & Caribbean | |||||

| Chile | 18.05 | 15,346 | 8.5% | 80 | 87% |

| Peru | 32.17 | 6,572 | 5.1% | 76 | 78% |

| Middle East & North Africa | |||||

| Jordan | 9.70 | 4,130 | 5.5% | 74 | 91% |

| Kuwait | 4.14 | 29,040 | 3.9% | 77 | 18% |

| South Asia | |||||

| Afghanistan | 35.53 | 586 | 10.2% | 64 | 25% |

| Bangladesh | 164.67 | 1,517 | 2.4% | 72 | 36% |

| Pakistan | 197.02 | 1,548 | 2.8% | 67 | 36% |

| Sri Lanka | 21.44 | 4,065 | 3.9% | 77 | 18% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||

| Benin | 11.18 | 830 | 3.9% | 61 | 47% |

| Ethiopia | 104.96 | 768 | 4.0% | 66 | 20% |

| Mali | 18.54 | 825 | 3.8% | 58 | 42% |

| Nigeria | 190.89 | 1,969 | 3.6% | 54 | 50% |

| Sierra Leone | 7.56 | 499 | 16.5% | 54 | 42% |

| Uganda | 42.86 | 604 | 6.2% | 63 | 23% |

Source: World Bank

Reliability assessment: Methods to do a quantitative comparison

To extend the GDHI to countries that have not yet reported on the platform, a series of comparator indicators were developed based on the World Economics Forum's Networked Readiness Index (see Figure 1 and Table 2). Indicator criteria were defined as follows:

- Must relate to the GDHI indicators

- Must be available for most, and ideally all, countries on an annual basis

- Must be translatable to a 5-point scale in order to develop a comparative maturity model

Three World Economic Forum (WEF) pillars, supported by 17 indicators and feeding into two sub-indexes, were identified from the Networked Readiness Index as meeting these criteria; the framework roughly corresponds to the WHO/ITU building blocks around which the GDHI is structured. While the WEF Network Readiness Index does not focus exclusively on health, it is designed to broadly measure how countries are performing in the digital world. A wide range of data is used to populate the index, including utilizing data from international agencies (e.g., UN agencies and the World Bank), as well as collecting opinions from more than 14,000 business executives located in more than 140 countries.

Figure 1: Comparative indicators for GDHI extension and reliability assessment

The three pillars selected for this analysis are the (1) political and regulatory environment, (2) infrastructure and digital content, and (3) skills . The political and regulatory environment pillar assesses the extent to which national legal frameworks promote ICT penetration and the safe development of ICT business practices. This includes intellectual property protection, software piracy rates, and efficiency of legal frameworks. The infrastructure and digital content pillar provides information on the ICT infrastructure including electricity, mobile network coverage, international bandwidth coverage, and secure internet servers. Lastly, the skills pillar evaluates the extent to which a society can effectively use and potentially benefit from ICT based on the quality of education, secondary education enrollment rate and literacy.

Table 2: GDHI extension and reliability assessment indicators

| Indicator # | GHDI Indicators (in 22 countries) | Proposed comparator indicators (in 149 countries) |

| Categories 1-3: Leadership and Governance / Strategy and Investment / Legislation, Policy and Compliance | ||

| 1 | Digital Health prioritized at the national level through dedicated bodies/mechanisms for governance | WEF Networked Readiness Index, Pillar 1: Political and regulatory environment (comprised of 9 indicators) |

| 2 | Digital Health prioritized at the national level through planning | |

| 3 | National eHealth/ Digital Health Strategy or Framework | |

| 4 | Public funding for digital health | |

| 5 | Legal Framework for Data Protection (Security) | |

| 6 | Laws or Regulations for privacy, confidentiality and access to health information (Privacy) | |

| 7 | Protocol for regulating or certifying devices and/or digital health services | |

| 8 | Cross-border data security and sharing | |

| Category 4: Workforce | ||

| 9 | Digital health integrated in health and related professional pre-service training (prior to deployment) | WEF Networked Readiness Index Pillar 5: Skills (comprised of 4 indicators) |

| 10 | Digital health integrated in health and related professional in-service training (after deployment) | |

| 11 | Training of digital health workforce | |

| 12 | Maturity of public sector digital health professional careers | |

| Categories 5-7: Standards and Interoperability / Infrastructure / Services and Applications | ||

| 13 | National digital health architecture and/or health information exchange | WEF Networked Readiness Index, Pillar 3: Infrastructure (comprised of 4 indicators) |

| 14 | Health information standards | |

| 15 | ||

| 16 | Planning and support for ongoing digital health infrastructure and maintenance | |

| 17 | Nationally scaled digital health systems | |

| 18 | Digital identity management of service providers, administrators, and facilities for digital health, including location data for GIS mapping | |

| 19 | Digital identity management of individuals for health | |

With the three pillars and their supporting indicators identified, country level data was pulled for all 139 countries from the WEF website in September 2018. Each indicator and pillar data point is scored on a scale of 1-7. For each country, the average score across the three pillars was calculated. The scores were then re-indexed on a scale of 1-5, and rounded to the nearest whole number. For the countries not included in the WEF database, the median index from countries in the same region and with the same World Bank income classification was used as a proxy.

In order to assess reliability, indicator 15 of the Global Digital Health Index, which is the overall WEF Network Readiness score, was removed to retain independence across measures. Indicator 16 thus become the sole contributor to Category 6, and Category 6 assumed the value of Indicator 16. GDHI category indicators were then averaged and compared directly to the WEF categories, before an average of categories was taken for both indices and rounded to return a single value.

Results of the reliability assessment

Following the analysis of the comparator indicators, the self-reported GDHI country maturity levels were compared to the WEF comparator indicators (see Figure 2). Twelve countries (or 55%) had a GDHI score equivalent to the comparator, and 5 countries (or 23%) had a GDHI score of one level higher than that of the comparator. Of the five remaining countries, two (Kuwait and Mongolia) had a GDHI score one level lower than that of the WEF comparator analysis. Two countries (Mali and Bangladesh) had GDHI maturity two levels higher than that of the WEF comparator analysis, and one country (New Zealand) had a GDHI maturity two levels lower than that suggested by WEF comparator analysis. The correlation co-efficient is 0.43 and the R-square value is 0.19.

Figure 2: Maturity level comparison

Discussion and Conclusion

For the reliability assessment, the lower-than-expected correlation can primarily be explained by two important, related factors. It is notable that out of 22 countries, only three GDHI scores are lower than the WEF comparator analysis score whereas eight GDHI scores are higher. GDHI is self-reported and tailored to a specific context (digital health) whereas the WEF comparator indicators are based on indices from a third-party source (notably with some qualitative inputs) and not sector-specific. Context-specific data may yield more accurate results, and digital health may be ahead of generic trends in local digital landscapes. Second, self-reported data often yields more positive results than third-party data, and may also in part explain the general trend of countries reporting higher GDHI maturity levels. Finally, since only whole values are used in both 5-point maturity level assessments, a one-level difference in maturity quantitatively translates to a 20% difference on a five-point scale. Whole values with such large differentials can distort correlational calculations and understate concordance between assessments. For these reasons, the fact that 19/22 countries were within one level of maturity is a stronger indication of concordance than the correlation coefficient and r-square values.

The new global digital health index, presented in this analysis, is a useful extension to the GDHI for several reasons. First, the analysis includes 139 countries as compared to the 22 currently captured in GDHI. Until more rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments are resourced and institutionalized, this model gives us an understanding of digital health maturity levels across a large cohort of countries. WEF indicators are uploaded annually, which is critical given the rapidly changing digital health field. Lastly, the new index does not exclusively rely on self-reported inputs making it an objective complement to self-assessment-based models.

Unfortunately, in a world without rigorous and country-led maturity model assessments, this model has major limitations that must be carefully considered when using this information. First, the WEF indicators capture cross-sectoral information and do not account for the health sector being more or less mature than the overall ICT sector in a given country. Second, a country-level analysis has some value, but a more granular analysis would likely reveal more actionable findings. For example, there can be large sub-national variations (e.g. urban vs rural). Third, it's very possible that the concordance levels change as more countries contribute to the GDHI; 22 is not a large number and the correlation could look quite different if 50 or more countries contribute to the GDHI.

While there is a reasonable agreement between the GDHI and the extension, additional research is needed to identify a more comprehensive list of indicators to assess digital health maturity. Our hope is that these analytics inspire further investment and engagement in developing a world-wide, annually measured indicator of country digital health maturity that factors in both self-reported and objective measures.